“What you know about this

… what you know about that?

You ain’t never seen a nigger get whacked.”

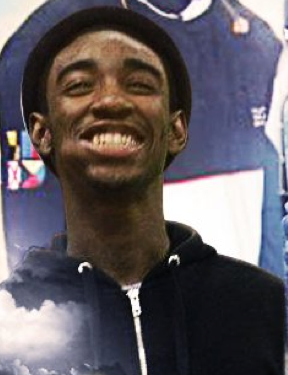

The words were assumed to be style, the rap of an 18-year-old from Southeast D.C. Talent and posture. But hours after performing the song, the writer, Navarro Anthony Brown, was dead.

Known by friends as “Moochie,” he was shot near his home in Anacostia on Jan. 10, 2012. Friends said he’d just left the recording studio with a girl he was interested in. An exhibit on Southeast D.C. life he’d been working on was due to debut at the Hirshhorn ArtLab Noise Factory.

“When they’re rapping, it’s really uncertain to tell when it goes from being real to stylizing,” Kate Clark, a visiting artist and mentor, said in an interview nearly a year after Brown’s performance.

“I assumed it was more style than document. But Moochie’s death made it all the more real.”

The artist, the creator

When Brown’s cousin, 24-year-old Chanice Coleman, found out he could rap, she was surprised by his talent because she always knew him as a “quiet guy.”

“I used to hear him mumbling with his iPod, but I didn’t know he could sound like that,” Coleman said. “The first time I heard him I probably laughed… he’s stupid goofy, had me laughin’ all the time.”

“I used to hear him mumbling with his iPod, but I didn’t know he could sound like that,” Coleman said. “The first time I heard him I probably laughed… he’s stupid goofy, had me laughin’ all the time.”

Others knew Brown only for his musical talent and said he was “hot.”

Among his friends at the ArtLab, a local digital media studio for teens, he was known as an artist, a creator, a producer, a writer and a rapper. Brown worked specifically in the Hishhorn ArtLab Noise Factory, a club designed to get kids experimenting with sounds and music, while learning about professional producing and recording software.

“He did the music, I did the music, that’s just how we got along,” said 20-year-old Joe Waker, one of Brown’s closest friends.

Waker said when he moved to a new high school, Brown was one of the first people to reach out and talk to him. Waker found out about the ArtLab, which was a free studio, and told him he had to check it out.

Waker said when he moved to a new high school, Brown was one of the first people to reach out and talk to him. Waker found out about the ArtLab, which was a free studio, and told him he had to check it out.

“After that, we just became cool,” he said.

Brown spent almost every day in December at the ArtLab, Clark said.

“Everybody had nicknames, and he made one for me the day that I met him. He called me KC Rose,” Clark said. “I’m a white woman who’s a bit older than them, so there’s clearly a cultural divide. It showed some maturity and generosity on his side.”

Clark worked closely with Brown and a small group of teen artists on a collaborative project, “Native Stars.” Together, they set out to collect and record the ambient sounds and raw voices of Anacostia in Southeast Washington.

“I was talking to Moochie about how to interview people, but he was pretty fearless,” Clark said. “There’d be some girls he wanted to flirt with, so he’d just go up to them and start asking them questions.”

“Native Stars” was to be featured in an art exhibit, “Visual Audio,” at the Honfleur Gallery, a contemporary art space in the historic Anacostia neighborhood of D.C.

Rob Peterson, a contributing artist in residency for a similar project in the Honfleur Gallery, recalled meeting Brown a few days before the opening.

“He was quietly inquisitive, and I could tell he was absorbing everything we were talking about,” Peterson said. “He was all smiles and seemed really inspired. Very polite, very mature.”

Moochie’s last night

One Tuesday evening Brown was in the ArtLab studio working on songs with Waker and entertaining the rest of the group with his fresh new piece.

Brown was incredibly playful that night, Clark said. He put projectors up, made himself the center of attention for a photo shoot, and rapped a bit to show off the new song he had finished that day.

At about 6 p.m., Brown left the studio.

“We just did a song, and I really wanted him on my next song that I was going to do, but he left with a young lady that I guess he was interested in,” Waker said.

According to court records, Brown was involved in an altercation with a teenage girl that night.

Michael Jerome Galloway, who lived in the neighborhood, recognized the teen as his friend’s sister, court documents said. He and Brown engaged in some sort of conversation, which ultimately led to Brown running away.

Galloway then shot Brown in the back of the head.

At 6:44 p.m., members of the Metropolitan Police Department responded to the 3200 block of 23rd Street SE, for a report of a shooting and found Brown bleeding from his head.

Brown was pronounced dead at 10:47 p.m. on Jan. 10, 2012.

Reaction

“I automatically thought nobody did it on purpose,” said Coleman, Brown’s cousin. “That was my first question: Who would want to kill Navarro?”

“Moochie had only been coming to the lab for a month, and he was there every moment from when the lab opened to when it closed,” Clark said. Another artist at the studio had told her, “He must have had some good time-managing skills if he was involved in some other shit.”

Brown’s friend Waker immediately left school when he heard the news and told his teacher he had a family emergency.

He saw police surrounding the area near a convenience store on Alabama Avenue where his group of friends often went.

“People act like they don’t know what happened,” he said. “I went around the street asking; I got all kinds of different stories. That’s how it is around the ‘hood.”

The shooting happened two days before the Honfleur exhibit opening. One of Brown’s pieces, “Native Stars,” was expected to be featured.

“We didn’t want to focus on the violence, the stereotypical things Anacostia is known for,” Clark said. “And then with the death happening, we obviously had to approach it in the project.”

Artists from the ArtLab collaborated with members of the Hishhorn Museum, deciding that everyone would start out at the ArtLab studio to pay tribute to Brown. Waker remained tucked away in the studio booth recording an RIP Moochie piece.

Eventually, the group took the 30-minute Metro ride together to the Smithsonian museum for a gallery opening in honor of their lost friend.

“How many times has a Smithsonian Institution been used to host a memorial for an 18-year-old boy from Southeast DC…?” Clark later wrote in a personal essay.

“It was one of the transformative actions of my lifetime to bear witness to young kids dealing with the violent loss of their friend and collaborator,” Peterson said. “The vacillation of emotions, the waves of grief, silence and violent outbursts were intense to watch come in weird rhythms.”

Sentencing

Seven months passed before then 18-year-old Galloway was arrested for killing Brown.

During the investigation, a witness provided information that connected Galloway to the homicide, according to court records. Galloway was searched, and two bags of marijuana were recovered. He was arrested and ultimately admitted to shooting Brown.

In September, Galloway pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter while armed and simple assault. Under sentencing guidelines he would face seven to 15 years in prison.

Two months after Galloway accepted the plea offer, Judge William Jackson sentenced him to the maximum penalty of 15 years.

“What turns the table for me is how senseless this was,” Jackson said. “This was not a fist fight, this was not self-defense. This was someone running away and you shot him in the head. I can’t get past that.”

“One person dead, the other behind bars,” Jackson added. “What a terrible waste that is.”

Galloway told Brown’s family, “I wish I could go back and change it.”

Aftermath

“He was just all around the best you can bring out of this neighborhood,” Brown’s mother, Monice Brown, said of her son. “We were so close.”

Brown was one of 37 people killed in Southeast D.C. in 2012. Seven other 18- or 19-year-olds died in the District.

Now living in New York Peterson laments how matter-of-factly deaths like Browns take place.

“You could throw a stone from one side of the river to the other. It’s not a very big river,” Peterson said. “And still, nobody knows what goes on over at the east side of the river. Moochie will probably remain anonymous unless somebody gets a hold of his story.”

“The way people take people’s lives over material things and stuff like that, or over words… it’s just crazy,” Brown’s close friend Waker said. “It felt like he could have stayed with me, he could have finished that last song…”

This story has been updated to include a quote from Navarro Brown’s mother, Monice Brown. The section on Michael Galloway’s sentencing has also been edited.